Observers have been puzzled by the continued strength of the U.S. stock market, asset prices generally and the U.S. economy in the face of sharp rises in interest rates since early 2022. Artificial stimulus from record U.S. budget deficits seems to be part of the cause, but an even more significant indicator is the velocity of M2 money supply, still one third below its pre-2008 historical level. With too much money in the system, asset bubbles and inflation are inevitable. Correction of this will produce a major slump, probably after the inauguration of the next President in January 2025. If that President is Donald Trump, the slump will not be his fault.

When you look at the ordinary graph of M2 money supply, it does not look too dangerous. There is a rapid 20% increase in M2 in the spring of 2020, when the Covid-19 outbreak hit, then it increases at a modest rate until spring 2022, after which it flatlines as the Federal Funds rate is pushed up from near zero to its current range of 5.25-5.50%. Based on M2, you would expect inflation to be currently close to returning to the 2% level, although it remains questionable whether the Fed should have continued raising rates until they were around 7% as monetary policy is not currently tight.

However, that does not explain the extraordinary ebullience in stock markets, with the Standard and Poor’s 500 Index bringing a total return of 22.7% in the twelve months to April 30, taking its return to around 71% over the 5 years April 2019, itself near the top of a 10-year bull market. Clearly, conditions in the stock market and the U.S. economy are far more favorable than would be suggested by the Biden administration’s lackluster economic policies and incessant meddling regulation, especially combined with the sharp rise in interest rates (which is already causing difficulties in city center office property and the private equity markets). The only explanation must be that there is still far too much loose money sloshing about, to put it non-technically.

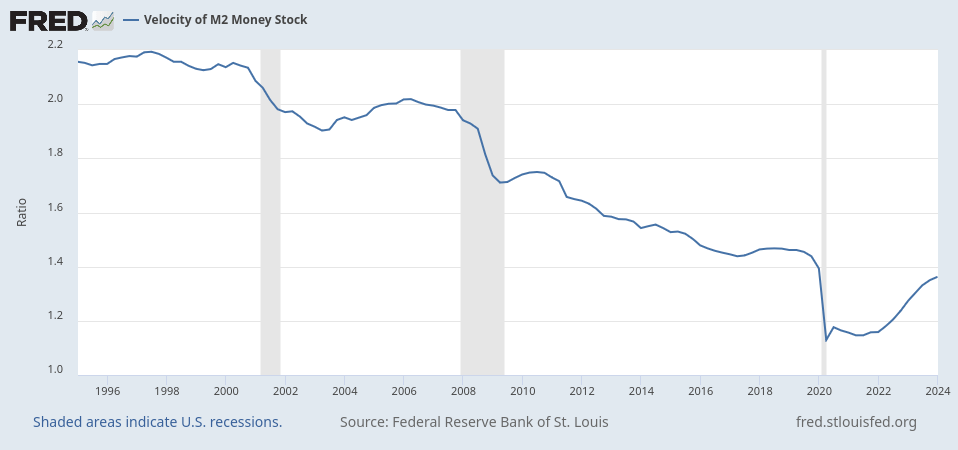

When you look at the velocity of the M2 money supply, shown here for the period since 1995 in the very helpful economic graphs of the St. Louis Federal Reserve’s “FRED” database, the problem becomes clearer. (For the non-technical, the “velocity” of M2 money supply is roughly Gross Domestic Product divided by M2 money supply; it is a measure of how quickly money whizzes round the economy.) You would expect money velocity, whether of the narrow M1 measure or the broader M2, to increase over time, as the payments system becomes more efficient, with stock market settlements having moved from T+3 days to T+2 days, for example (and quickening further to T+1 day later this year). The actual graph shows clearly the effect of Bernankeist monetary policy since the financial crisis.

M2 Velocity was pretty steady at about 2.1 in the late 1990s, having been around 1.8 before 1990. Then it dropped slightly to 1.9 in 2000-07, reflecting the somewhat lower efficiency of the sluggish George W. Bush economy compared to the 1990s boom. Then Ben Bernanke became Fed chairman and flooded the system with “quantitative easing” liquidity, causing an initial lurch downwards to 1.7 in the 2008-09 recession, then no recovery but a steady further decline, to 1.39 in the first quarter of 2020, just before the Fed’s injection of extra money. The ratio dropped sharply again to 1.13 in the second quarter of 2020, a far sharper drop than in 2008-09 in a much milder recession, then recovered, first sharply and then more slowly. However, it has only returned to 1.36 in the first quarter of 2024, still below the level of early 2020, despite the Fed having been restrictive in its interest rate policy. Today, M2 velocity is more than a third below its level of the late 1990s and around 28% below its level of 2000-07, despite the massive advances in financial processing technology we have seen in the last quarter-century – it is perhaps 40% below where it should be.

A similar pattern recurs in more extreme form when you look at M1 monetary velocity (M1 being smaller than M2, the massive stimulus by the Fed had more relative effect). Here M1 velocity rose from 6 to 9 in the late 1990s, then soared further to almost 11 by the end of 2007 – Greenspan and Bernanke were goosing the economy by artificially low interest rates but not at that stage printing money directly. Then with the Bernanke “quantitative easing” stimulus it fell to 5.33 in the first quarter of 2020, before dropping over a cliff to a low of 1.25 in the first quarter of 2021. The recovery here has been only modest, to 1.57 in the first quarter of 2024, less than one fifth of the late 1990s level, indicating that there is still a grossly excessive amount of money sloshing around in the U.S. financial system.

There are a number of sources that generate all the extra money. The Fed in its folly injected some $8 trillion of “quantitative easing” stimulus into the economy in 2009-20 by buying Treasury and Agency securities, on the funding of which it is now paying 5.5% to the big banks. It has sold just over $1 trillion of these, but still owns $6.9 trillion of them, so the big banks still have this entirely unnecessary subsidy on their balance sheets. In any case, the Fed announced at its meeting May 1 that it would slow the sale of these assets, so the subsidy to the big banks will remain. Bear in mind that the big banks pay almost zero on their demand deposits, so the 5.5% is “free money” – it is little wonder the big banks have almost ceased lending to small business, which they see as too much like hard work.

Apart from the budget deficit generally, there are two other gigantic subsidies from the Biden administration, with which it hopes to keep the tottering Jenga tower of the U.S. economy upright until November 5. (Will the impending stock market collapse remove the key brick before then? – watch this space!) One is well known: the repayment by the government of successive waves of student loans for 30 million borrowers, at a total cost of around $600 billion. This direct bribe to the electorate will inject new purchasing power into the economy, as the ex-students relieved of debt payments go out and spend the money, or possibly use their improved credit ratings to borrow from third parties.

The other, very likely with a larger effect on immediate consumption, is the decision last month to allow Freddie Mac to make home equity loans. According to an enthusiastic article in the Financial Times by “Oracle of Wall Street” Meredith Whitney, this will provide “stimulus” to the economy by allowing homeowners to tap the $32 trillion in home equity on their personal balance sheets “adding not $1 to the national deficit.” Ms. Whitney estimates that $980 billion of home equity loans could be unlocked in the short term by this move, much of it to senior citizens who cannot currently pay their bills, a group left almost untouched by Biden’s student loan debt relief. Of course, much of this additional “stimulus” will be generated before the November election, and like the gender studies majors unburdened of debt, Biden hopes the impoverished senior citizens will be duly grateful.

This is terrible news. As discussed above, the last thing the U.S. economy currently needs is more “stimulus” – it is already operating at a thoroughly artificial level. Freddie Mac and its sister agency Fannie Mae cost U.S. taxpayers some $150 billion by their dozy lending on subprime mortgages before the 2007 financial crisis. The default rate on second mortgages is notoriously higher than on first mortgages, and Freddie Mac will no doubt find ways of ensuring it gets the very worst loans through the adverse selection that generally afflicts enthusiastic new entrants into an already well served loan market.

As for the impoverished senior citizens, they will no doubt enjoy the first six months after receiving the proceeds of their second mortgage with a spending spree, possibly including a vacation trip to the local casino. Later, with first and second mortgages to service and the same inadequate income they had before, they will be forced out of their homes and onto the street. Far from a “win-win-win” as the ebullient Whitney describes it, this proposal is a “lose-lose-win-collapse” with the win being to Biden’s meager vote total in November and the collapse being the U.S. economy after the defaults roll in.

“Madmen in Authority” said Keynes, no doubt referring to successive Chairmen of the Federal Reserve. We are about to see the long-term result of their madness, albeit almost certainly after the November election. When it comes, don’t blame President Trump!

-0-

(The Bear’s Lair is a weekly column that is intended to appear each Monday, an appropriately gloomy day of the week. Its rationale is that the proportion of “sell” recommendations put out by Wall Street houses remains far below that of “buy” recommendations. Accordingly, investors have an excess of positive information and very little negative information. The column thus takes the ursine view of life and the market, in the hope that it may be usefully different from what investors see elsewhere.)