The appalling interaction of opinion polls and TV debates is yet again pushing the Republican party to produce a poor-quality Presidential nominee, the eighth in succession (well, to be fair, Mitt Romney by a magnificent, sustained effort rose all the way to mediocre.) Likewise the Labour party’s prolonged election of the eccentric leftist Jeremy Corbyn has caused many party elders to wonder if there is a better way (though Conservative party elders have much enjoyed the process.) There is only one solution to this problem: we must return to the “smoke-filled room.”

The “smoke-filled room” was the suite in Chicago’s Blackstone Hotel in which during the early hours of June 11, 1920, Warren G. Harding was selected by party elders as the Republican party’s presidential nominee. Interestingly, the location of the original suite is not properly nailed down. The earliest source I have seen, from 1948, says it was the fourth floor suite booked by the tycoon/magazine editor George Harvey, probably three rooms numbers 408-409-410 (though another source says 404-405-406.) The hotel itself, now under Marriott Renaissance management after a major renovation, appears to believe the ninth floor suite 914-915-916 was the location, while other sources locate the suite on the 8th or the 13th floor.

I know of no way of determining the reality; it’s quite likely that nobody took note of the room number at the time, so both the 1948 source and the modern renovators may have got it wrong. Certainly there is no reason why it should have been immediately under the 10th floor Presidential Suite, as the renovators would have us believe – Harvey was a big shot, but there were many such in the 1920 Republican party, and the one thing we can be sure of is that the Presidential Suite was not on that weekend occupied by the President, Democrat Woodrow Wilson.

Harvey is an interesting figure as the sponsor of the smoke-filled room. In earlier life, he had been Managing Editor of the Democrat New York World, who had then made a fortune re-organizing the streetcar lines in Havana, Cuba after the U.S. conquest of the country in the Spanish-American War. In the years after 1906 he had sponsored the political career of Woodrow Wilson, only to be thrown over when Wilson decided to run for President and moved left. Thus he had “form” in selecting Presidents, and may well have played an active role in steering the relevant Senators and big-wigs to the smoke-filled room, and possibly in the discussion that took place there. While favoring a “dark horse” compromise candidate between the leading Republicans who had deadlocked the convention, he is said to have preferred Will H. Hays, chairman of the Republican National Committee, to Harding.

Harding is generally regarded as a poor President, but that’s because the Left writes the history books. In reality, there is surely no question that he was better than any modern President since Ronald Reagan. He solved the 1920-21 recession mush more effectively than his successors solved the 1929-32 one. He established the United States as an involved and benign participant in the global geopolitical system, without joining Woodrow Wilson’s foolish poorly-structured League of Nations. He ended the persecutions of the last Wilson years, both against the Left and more notoriously against African-Americans. Most important, with Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon he established a pattern of cuts in government spending, control of government waste (he established the Office of Management and Budget) and reduction of government’s involvement in the economy that his successor Calvin Coolidge was to continue to the great benefit of all Americans.

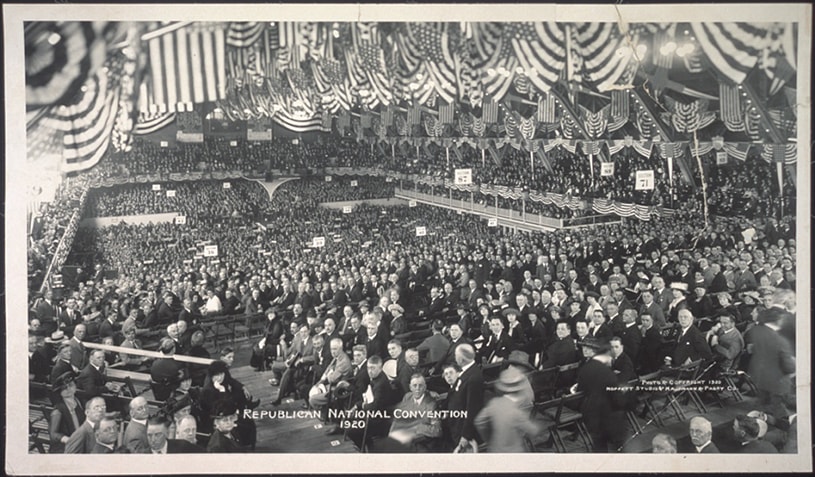

The process that selected Harding included a few primaries, but consisted mostly of state conventions selecting delegates to a national convention, whose votes were then steered by local and national party leaders. It had the advantage that most of those involved knew what they were doing; the delegates to the convention, even if bound by a primary to cast their first ballot for General Leonard Wood or Illinois Governor Frank Lowden, were mostly political junkies, with a political junkie’s knowledge of the other available candidates. Indeed, after they had selected Harding, the delegates themselves rejected the bosses’ choice for Vice President and made the inspired selection of Massachusetts Governor Calvin Coolidge.

Theoretically today our process, evolving in the years after 1920 and then changed through “reforms” following the 1968 election, is more democratic with candidates selected by the full range of party supporters in a series of state primaries. The new selection method worked quite well for the first couple of trials, those selecting Jimmy Carter for the Democrats in 1976 and Ronald Reagan for the Republicans in 1980. However since 1980 it has morphed into a system in which the primaries are increasingly irrelevant except for the first few and most of the selection takes place during a pre-primary period governed by opinion polls and debates.

In today’s system this year, the two GOP candidates with the best governing resumes, Rick Perry and Scott Walker, have been the first to drop out. Perry’s exit is especially egregious because participation in the debates was governed by opinion polls, taken more than a year before the election, and highly inaccurate at the low end, where the distinction between the tenth and eleventh strongest candidate for the first debate was made. That’s even assuming the polls themselves are untainted by methodological or political bias within the polling companies.

As for the debates, actual performance is pretty well irrelevant compared to the media spin afterwards. I watched the undercard first debate and the main second debate, and in neither of them did I think Carly Fiorina distinguished herself. The first undercard debate was clearly “won” by Perry, to the extent debates can be won or lost, whereas by far the most impressive performances in the second main debate were from Marco Rubio and Rand Paul. Fiorina came across as shrill and unpleasant in both cases, with a grasp on foreign policy that was both simplistic and excessively belligerent. Yet in both cases the media anointed Fiorina the winner, giving her a massive boost in the polls. (Though who knows whether this will last – I am not a clairvoyant in this very obscure and un-transparent process.)

A process that weeds out two of the best qualified candidates before a vote has been cast is not democracy, nor is it working. The principal characteristics needed to succeed in this process are an ability to raise money (which as the Clinton Foundation shenanigans have shown, is highly likely to lead to massive corruption), an ability to impress the media in the numerous “debates” and an ability to shine in opinion polls taken months before a vote is cast. This puts the power of Presidential selection squarely in the media, the polling companies and the donor class, taking it away from the primary voters where it is supposed to lie. There is nothing whatsoever democratic about a system that takes power away from actual voters in this way and puts it in the hands of unelected insiders.

A better system would put the selection of Presidential candidates back among the people who know most about them, the party activists and other political junkies, together with the Senators, Congressmen and Governors at the center of our political life – in other words, it would bear a considerable resemblance to the system that selected Harding in 1920. If there were primaries (as there were in 1920, the result of Progressive reforms) they would be few and minor, and their results would not be binding on the party as a whole. (We do not seem to have missed much by losing the Presidencies of Wood and Lowden, the primary winners in 1920 – Wood, after a distinguished military career, was a big supporter of the civil liberties violations of 1919-20, while Lowden served only four years as Governor of Illinois, his term being notable for the 1919 Chicago race riots.)

Under the new system, after a modest number of primaries, and local processes selecting delegates, presidential candidates would be selected by the convention, which would be held in May/June. Vast quantities of money would not be needed, since the primaries would be fairly unimportant and advertising would be irrelevant to convincing the politically knowledgeable delegates at the convention. In some years, a candidate would do well in the primaries and in delegate selection and would arrive at the convention with majority support on the first or second ballots. That would probably have been the case for George W. Bush in 2000, for example.

In other cases, as in 2008 and 2012, several candidates would arrive at the convention with substantial regional or ideological support – perhaps John McCain, Mitt Romney, Rudy Giuliani, Mike Huckabee and Ron Paul in 2008; probably Romney, Rick Perry, Newt Gingrich, Rick Santorum and Paul in 2012. When this happened, as in 1920, the party leaders would get together in a room and decide which of the candidates the convention should support. Presumably the room would not be smoke-filled, although for a Democrat convention it might be filled with weed smoke, rendering the leaders’ decision-making process especially eccentric.

My guess is that with this selection mechanism Romney might have won in 2008, handling that autumn’s financial meltdown about as well as anyone could, and better than did McCain, Obama or the incumbent George W. Bush. In 2012 Perry, recovered from his back problem and untainted by debate stumbles, might have been the winner – with a better chance than Romney against Obama that November. Next year, who knows – but Perry and Walker would be serious candidates, and Donald Trump, Ben Carson and Fiorina would not be. As for Jeb Bush, since the party big-wigs would want to win in November 2016, they would probably avoid him.

The present system is broken. The previous “smoke-filled room” system worked quite well and was in its way more democratic. Let’s go back to it.

-0-

(The Bear’s Lair is a weekly column that is intended to appear each Monday, an appropriately gloomy day of the week. Its rationale is that the proportion of “sell” recommendations put out by Wall Street houses remains far below that of “buy” recommendations. Accordingly, investors have an excess of positive information and very little negative information. The column thus takes the ursine view of life and the market, in the hope that it may be usefully different from what investors see elsewhere.)